Richard Serra at David Zwirner

In the dumbest century, Serra continues to do the most ridiculous thing: he makes quality works of art

“Richard Serra: Drawing”

May 4 - June 18

”Richard Serra: Sculpture”

May 4 - July 15

David Zwirner, West 20th Street, New York City

Richard Serra (b. 1939) has the unique distinction of having been controversial for reasons entirely of material and form. Not his behavior (Picasso’s philandering), not his imagery (the Mapplethorpe and Serrano photographs that triggered the cons in the last culture war or Schutz’s appropriation of the image of the slain Emmett Till): his actual art. In the ‘80s, Serra infuriated downtown government workers with Tilted Arc, which poetically but inconveniently bisected Foley Square: a petition was launched for its removal and grievances were aired at a 1984 public hearing.

The only thing I’ve seen lately and really enjoyed — sorry pomos, I do think that pleasure, even ugly pleasure, is a necessary component in aesthetic experience — were Richard Serra’s twin shows at Zwirner: “Richard Serra: Sculpture” and “Richard Serra: Drawing.” It feels a bit like a cop out. Serra’s quality is well established. As the great critic Michael Brenson wrote of the artist at his most controversial:

The work has provoked so much enmity in part because it can seem to thump its chest, raise its fist and pound its way head down across the pavement. Its remarkable attentiveness and versatility emerge slowly. ''Tilted Arc'' is confrontational. But it is also gentle, silent and private. It is an intimidating block of steel, but it is also a line, a bolt through space. It does seem to be breathing down on us, but it also lies down and shuts up and offers us a refuge. Almost always, it seems to be gesturing, reaching out - speaking - asking us to consider where we are and what we think. The repeated claims at the hearing that Mr. Serra did not take the plaza and Foley Square into account are absurd.

What also makes ''Tilted Arc'' appropriate to its site is its content. The work has a great deal to do with the American Dream. The sculpture's unadorned surface insists upon its identity as steel. The gliding, soaring movement recalls ships, cars and, above all, trains. As with many enduring works of American art and literature, behind the sculpture's facade of overwhelming simplicity and physical immediacy lies a deep restlessness and irony.

Restless, yes, but what Brenson called irony in 1985 I’ll call pleading romanticism. “Sculpture” lands a steel cylinder in a present more mystified by it — and itself — than ever. “Drawing” romances the mark, applied here in black paint stick with the semblance of hot asphalt, as a plan best laid by mice and men. Of course I liked Serra. Slow news day, eh?

It is kind of a slow news day, or year, or decade, or century, is it not? The bi and tri -ennials are a yawn. Funny things are afoot in the market, which has lost interest in what the old academic elite say is valuable. And no wonder. In the academy, Jason Farago writes, “the tone right now is stubbornly backward-looking, capable of little beyond auto-critique and enduring a bona fide crisis of confidence.”

In the void where aesthetic quality once was, there is “speculative hype” measured in dollars and cents. Blue chip art tends toward the vapid: “zombie formalism” and “bad figurative painting.” The visual quality is in play at least, even if it sucks. Conceptualism is delighted to dismiss beauty as a dated endeavor and too often treats the visible as an afterthought. Was the attack on the concept of “quality” (and “aesthetics” and “value”) in art theory from the late 20th century onward a mistake or a coping mechanism? Postmodern theory excels at selling new arrangements of unfreedom as liberatory propositions. Don’t worry, fellow intellectuals, we queered the Pinkertons.

Prestige TV is as formulaic and predictable as the sitcom and worse, chasing a cloying earnestness that oozes through the screen like syrup. A trailer for a Game of Thrones sequel (because the first one went so great) shows a woman solemnly saying to another, “Men would sooner put the realm to the torch than see a woman ascend the iron throne.” I’m not sure if you caught that very subtle reference, it was easy to miss. It’s about feminism. Get it? Because men don’t want a woman on the throne?

These Splenda politics seem, finally, to be losing their appeal. Good riddance to the age of pious sincerity. As the cultish faith in the politic-ish monoculture of urban liberals breaks down we discover that we all just kind of like different things and maybe that’s OK. But then there are no different things. Doddering blandness, executed by armies of administrators terrified of causing anyone offense, has won the day. In hindsight, the poptimism that emerged in reaction to 2000’s hipster douchebaggery was not so wise. It gave us a parade of must-see water cooler dramas that in turn produced endless cultural reportage, but nothing of substance. It turns out that the aughts hipsters’ most annoying trait was also their best: they cared — very much, often stupidly and for stupid reasons — about quality.

Quality isn’t really part of the visual art conversation these days. Works of art “succeed,” or so we tell ourselves, on their virtues: what they’re for or against. But for Serra, an octogenarian white guy minimalist sculptor, virtue and identity just ain’t gonna cut it. So he continues to do the most ridiculous thing: he makes quality works of art.

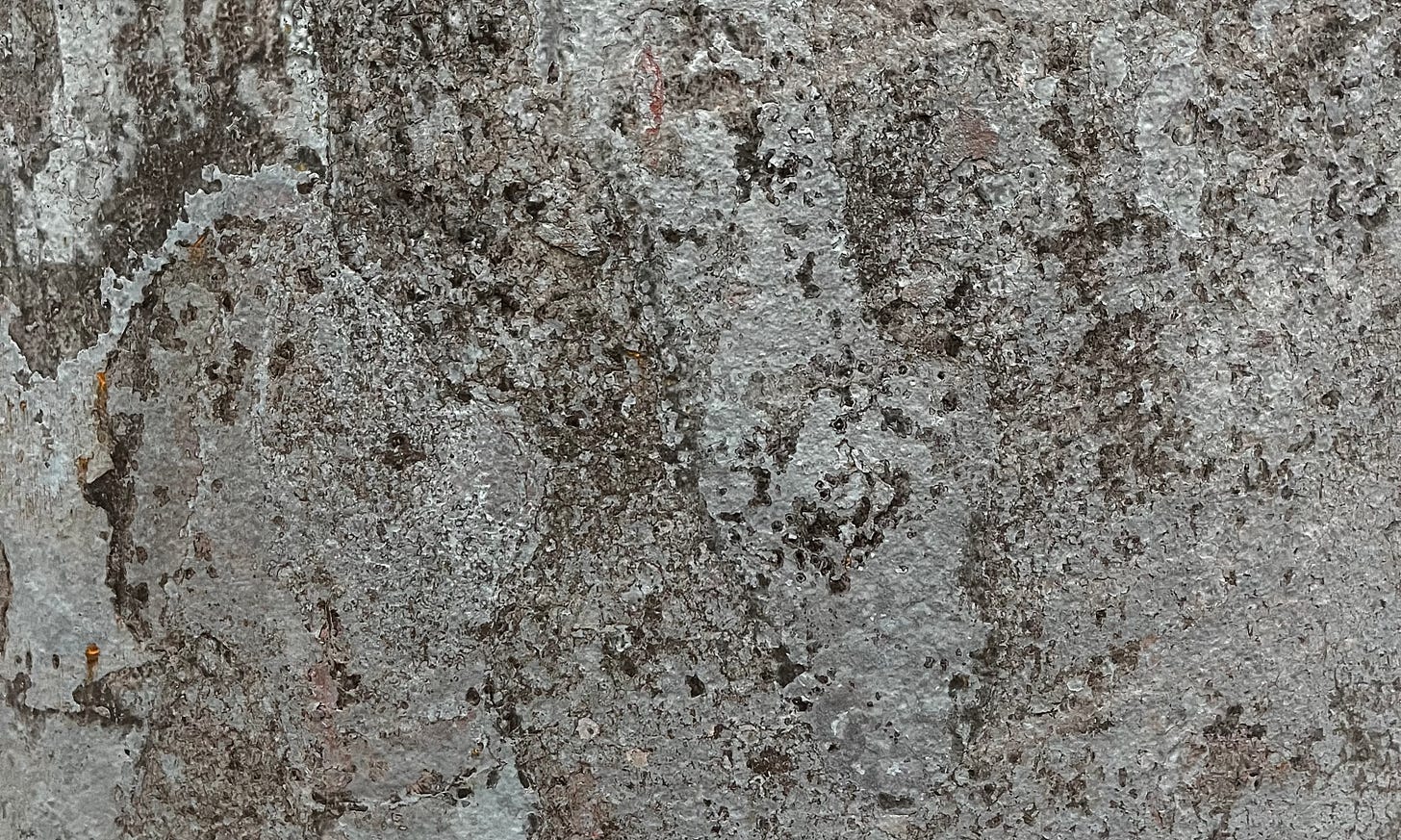

I have my reservations about the sculptures for which Serra is most famous: vortexes of steel that the viewer walks into, emerging from narrow passageways into a womblike inner sanctums. I’m willing to give him a pass here. His sculpture at Zwirner inverts his mazes: the viewer once again views. I instinctively circumambulate the massive cylinder in the center of the gallery, then watch as the other visitors do the same. There’s a suspicious holiness to it, but I’ll take it. Put anything in the middle of a white cube that large and it will seem profound. It is beautiful, though. Achingly so. The extraordinary gravitational weight of the cylinder is animated by the warm undulations in texture and subtle gradients on its surface.

By 1967, critic Michael Fried sensed the gravity of this new gravitational sculpture. The “whole situation” comes into play, he wrote unhappily in Artforum, in forms that shift as the viewer walks around them, dislocating art from object and rendering the situation theatrical. But the chaos did not stop there. By the end of the very Artforum issue in which Fried argued his case for presence against theatricality, Sol Lewitt issued the fatal blow: “The idea is the machine that makes art.” Minimalism became conceptualism, even theatricality became quaint. The fact that visual art is no longer visual is the inheritance of this moment, which Lucy Lippard triumphantly called “the dematerialization of the art object” and Hal Foster more soberly termed “the crux of minimalism.” Like the dwarves of Moria the artists of the midcentury dug too deep in their search for Art with a capital A and found a monster instead.

The drawing Circle (1975/2011) is visually arresting to the point of terror. Craggly paintstick black smears over the entire round surface leaving no margins, no guardrails. Upon approach it transforms from a black hole to an undulating surface.

The temptation to call the drawings sculptural must be avoided. Serra is deadly serious about medium. Unlike Judd, who conceived of his art as beyond the categories of painting and sculpture, or Lewitt, who subordinated the whole affair to “the idea,” Serra’s work in both drawing and sculpture is ferociously medium specific. It’s the sheer audacity of sculpture to shape space itself, intrinsically and extrinsically. His drawings exploit the boldness of the mark made only for its own internal purpose. They prepare for and represent nothing. They invent their own necessity.

Asking what constitutes drawing or sculpture will strike many students of art as a dated question. Conceptualism and multi-media installation art long ago swept that kind of ontological inquiry aside. But was this a resolution of the question, or an evasion? If there is nothing unique to sculpture, or drawing, or painting, what is unique to art? What basis exists for its necessity?

Zwirner’s website leads with photos of Serra’s cylinder in production, glowing red hot and malleable, surrounded by hard hats. Even heavy industry feels like a thing of the past. It still exists, of course, but for most Americans it is so peripheral that we believe commodities materialize on the Amazon delivery van. The American artistic fascination with industrial material came as American industry was in decline, a process that was already underway in the late ‘60s when Serra et. al began appropriating its techniques and materials. The emphasis then was on art as labor, artist as worker. They were not yet fully conscious of the fact that their art materialized absence: of steel workers, hard hats, and decently paid union jobs.

Now we have bullshit jobs and twitter fights — the kind of lifeless bureaucracy suffered by the workers infuriated by Tilted Arc. The heavy steel slash across a plaza of alienated government administration just hit too close to home. In this sluggish century academic conceptualism is arranged and rearranged, recycling the same material and ideas ad infinitum, and the cracks are really showing. Conceptualism has run out of steam. The concept of minimalist sculpture is a punch line repeated to oblivion. In Serra, the works are not reducible to concept and survive without it, beyond it. New ideas evade us. What remains possible is the mark, the form, the slight ripple in the steel, the splatter that wasn’t there before. It’s not much. But it’s something.