Last Friday, a group of artist activists launched paper planes from the top of the Guggenheim’s rotunda carrying the demand for a no fly zone over Ukraine. They garishly substituted the heavy bombers they called for with delicate folded flyers that floated softly to the floor: politics as childsplay. Museum protests, and their effective impotence, is nothing new, but this one stood apart: this was a pro-war museum protest.

I am deeply ambivalent about publishing this dispatch from the wrong life. I am an art critic. I have no business writing about the horrific Russian invasion of Ukraine. When we in the art world tie the import of art to its “relevance” we admit that we never really believed art to be important at all, just a tool in service of more pressing matters. Art succeeds precisely to the extent that it refuses to accede to reality by attempting to intervene in it. It has nothing to contribute to this discussion — this war. But dissolving itself into matters in which it has no business is now par for the course for tattered old art.

Museum protests, and the overdetermination of museums’ practical effects as politicish community service institutions by both protesters and museum leadership, tend to flare up when real political imagination is most impoverished and real aims seem most remote.

At the end of the 60s, as Harlem’s Black Emergency Cultural Coalition protested the Metropolitan Museum’s egregiously racist “Harlem on my Mind” exhibition (it contained no credited work by black artists), New Left-ish artists rallied at MoMA for better treatment of artists and free public access, and then against racism and sexism and the war in Vietnam. “It was just Joseph Kosuth pretending to be a Marxist,” Dan Graham later recalled.1 The following year, Robert Morris organized the New York Artists’ Strike Against Racism, Sexism, Repression and War. In the years to follow, feminists like the Guerrilla Girls would use museum lobbies as protest sites, and environmentalists discovered that museums are a very visible place to go after the institution’s oil-producing sponsors like British Petroleum.

The artists involved in the AIDS activism of ACT UP New York understood that they could wield their cultural leverage in the arts against the powerful figures denying or blocking action on the epidemic. When, more recently, Nan Goldin led the extremely rare effective museum protests against the opiate-producing Sackler family, she understood this arrangement. Tackling the Sacklers on their philanthropic home turf provided leverage and popular drive to federally prosecute family members. It was a media strategy with a purpose, and it worked.

At the 2019 Whitney Biennial, protesters took on vice-chairman of the board Warren Kanders after his ownership of a company that produced tear gas canisters used against migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border came to light. Artists withdrew their work from the Biennial as protests continued outside the museum, and Kanders eventually resigned. I wrote critically at the time that this was a pyrrhic victory, that ousting Kanders changed nothing about conditions at the border and would only succeed as the sideshow that eclipsed the actual art in the Biennial.

Museum protests, generally, are antagonistic to the interests of the capital that make museums possible. They’re adversarial. Toothless as it was, even the anti-Kanders protest was oppositional in spirit. This is what made Friday’s protest at the Guggenheim so startling. In the past, artists attacked board members’ financial interests in oil or defense. Here, the protestors encouraged them. Gone is the tension between the artists and the museum and its trustees; all eyes turn to the evil in the east. This wasn’t a protest. It was a rally.

It’s not just artists at the Guggenheim. Every facet of life and culture is now liquidated into politics, and politics liquidated into culture. On fashion websites I find more commentary on the invasion than tips on what this aging millennial should wear. Ukrainian and Russian performers on Pornhub are using their channels to speak to the world against the war in clips surrounded by a dozen or so frames of genitals. Not even masturbation is spared. The technology that brought you immersive Van Gogh will soon bring you immersive Ukrainian Taras Shevchenko. There’s a rush on interviews with Ukrainian artists as art publications scamper for a take. And here I am doing it too, if only for the sake of pleading that others stop trivializing reality.

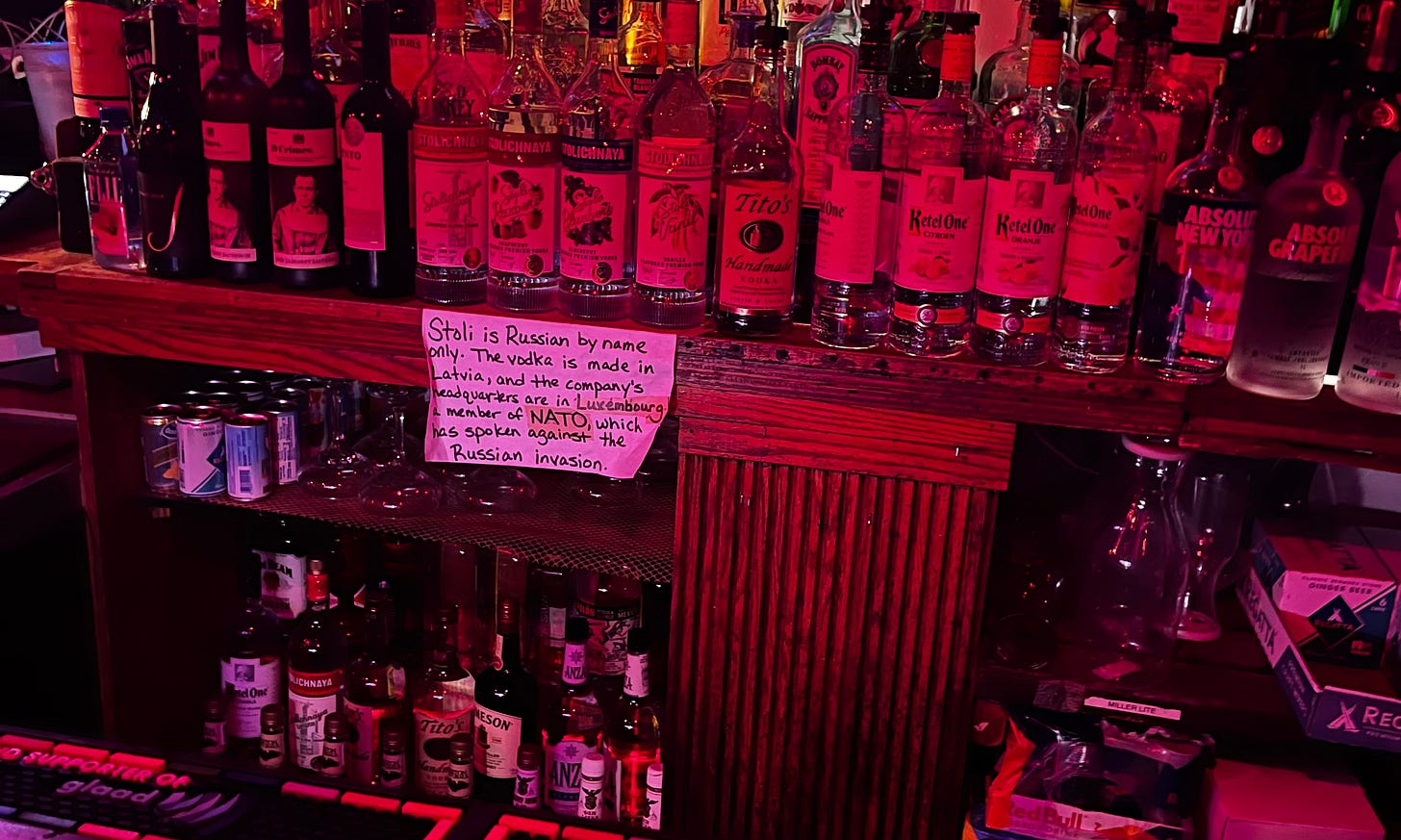

Florentines are petitioning to remove a Dostoyevsky statue. Orchestras are firing Russian performers and canceling Tchaikovsky concerts. (Neither the Russian novelist nor composer is presently living.) Russian nationals are being barred from sports events in the west. Museums are booting Russians from their boards and cutting ties with the country. A bar I frequent had to put up a sign explaining that Stoli Vodka is not produced or owned by Russians as bars and liquor stores purge their shelves of Russian products. It’s freedom fries all over again. This is mob indignation: moralistic culture wars posturing. The invasion of Ukraine is not a culture war. It’s a war. And yet the infantile theatrics of moral certainty and Twitter cancellations are rallying to it. The culture wars are going to war.

The total deployment of culture in the service of politics has historically done great damage to culture and little to its targets. The Vietnam War was not halted by art, but a whole lot of bad art was made in hopes of doing so. The action at the Guggenheim was shocking because, unlike previous museum protests, it aligns itself with the defense industry in favor of militarization. It is terrifying because it might actually get what it’s asking for.

He said this to me. You’re just going to have to take my word for it.